SHADOW DREAMS MURMUR

☞ Birds fly in black murmurs over the city, each following one rule: stay as close as possible to the bird next to you. Though no one leads, the group moves in undulating clouds, every small turn exponentially magnified. The roads of Kolkata follow a similar logic. Cars, buses, trucks, people, bicycles, animals, rickshaws, and other moving bodies swerve around each other in a high-stakes game of chicken, often passing with less than inches to spare. American highways push people forward in organized sheets. Here things move like water rushing out of a broken dam. I can't look out the window without wanting to hurl. This is the first time I’ve been back in the city of my birth in over ten years.

In a cramped white sedan we're hurtling toward Kumortoli, an enclave on the banks of the Ganges where artisans make clay statues of godessess all year. The car belongs to Gautam, a childhood friend of my parents. He is leaving tomorrow to make a documentary on the mental health of women in Punjab, but today he wants to know about the American left. Patrick and I laugh derisively at the question (who is the American left?) but still try to explain what is happening in the country we left behind.

If elections in liberal democracies are decorative blankets thrown over the sarcoid mass of oligarchy, this particular one was sheerer than Americans are used to. People are struggling to understand how to move forward as a cadre of devils take power. Today in America an Imperial Grand Wizard of the KKK was found dead. People are dancing on his grave and there’s tut-tutting from the center. It’s unseemly to celebrate death, even of the evil. Some weeks ago, protestors prevented a white supremacist from speaking at UC Berkeley. The university responded with beseeching emails about the importance of free speech, even for abhorrent ideas. Incidents of hate crimes have been rising in the United States alongside hate speech.

Expansive ideas like diversity are promoted with the goal of enriching human life. Those who would argue that millions of humans should be allowed to die in polio epidemics out of respect for the principle of biodiversity are not generally considered reasonable or compassionate. We inject our bodies with embodied knowledge in the form of mandatory vaccinations to inoculate us against the ravages of viruses like polio. This stops the spread of polio until it becomes a footnote in our collective consciousness. Soon, people start questioning the value of mandatory vaccinations. In war-torn countries where vaccination programs are difficult to administer, polio has once again reared its ugly head. Raw white supremacy is such a virus: a dormant parasite that activates during stress, using the functional apparatus of the very institutions it aims to destroy in order to reproduce itself. Each swell of effort to fight white supremacy is stymied by free-speech fundamentalists who wax philosophical about the inherent value of dangerous ideas. If your mind is too open, your brain falls out. Simplistic adherence to ideas like free speech indicates a model of reality that underfits a far more complex actuality.

We say some version of all this to Gautam. He is is sympathetic but seems skeptical. All ideologues are bad, he says. Kolkata is a failed Marxist state. The three of us stand quietly, watching a sculptor watching a sitting goose as he remakes its form in hay and slip clay. On the plane I had been reading a book by political forecaster Nate Silver. According to Silver, being a partisan makes for bad predictions. Now that the world is being turned upside down, there seems to be increased interest in warning about the dangers of partisanship and how it warps objectivity.

☟

It's strange how scientific language erases the historical and material context of things. "Partisan" doesn't refer to billions of dollars being shuffled around the world. It doesn't refer to the practice of redlining districts or jamming a highway through middle class black neighborhoods or moving the construction of an oil pipeline from a white town to indigenous burial grounds. It doesn't refer to the anger at being told that your position of power in the United States is unearned when you've worked hard your entire life and tried to honor God, or the fear of becoming the very minorities who you've praised many times for their work ethic and cuisine. Partisan refers to groups of people who have strongly held opposing points of view, to red and blue balloons.

In his book, Silver uses a Fox News commentator prone to making “as dramatic a prediction as possible” as an example of how partisanship ruins predictions. This commentator predicted that Donald Trump would run for Republican nomination in 2011 and had a “damn good” chance of winning it. He was wrong, of course. This event instead happened during the next election, a cataclysmic outcome that nearly no one, not even Nate Silver predicted.

A prediction is a statement about an uncertain event. A current theory supported by a wealth of experimental evidence proposes that consciousness is the sensation of the brain making predictions about the future using Bayesian operations. It theorizes that a neural process called predictive coding minimizes the dynamic range of input data in order to optimize processing power and maintain an accurate internal model of the world. An ideal model is complex enough to adequately explain the intricate interactions between various aspects of reality, but not so convoluted that it mixes up error and the truth. This internal model can be described as our worldview.

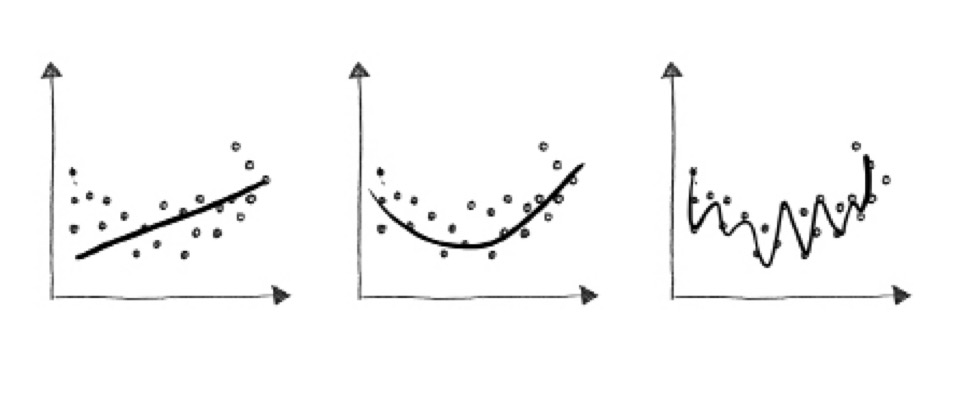

UNDERFITTING

IDEAL

OVERFITTING

As our senses keep acquiring new information about reality, the model is updated—not with the new raw data, because that would contain mostly redundant information (You have stopped noticing this innocuous tree on your front lawn that you walk past every night)—but with the degree of difference between the prediction and what is actually experienced (But you notice it tonight. The bark is marked with a red swastika). This difference is called a prediction error. This "error" is not necessarily a mistake, but describes how accurate a prediction was. A large value means that what the body sensed was wildly at odds with what the brain predicted it would (This is a tolerant and liberal city, this red mark on the tree is probably not a swastika). The brain then determines the precision of this error, or how reliable it is. It uses this value to regulate how heavily this new piece of information should influence the prior model. (Well, it is dark out—maybe you just saw it wrong. You’re not going to overreact and assume the worst). This last step is a mechanism for parsing signal-to-noise ratios—or distinguishing useful information from random fluctuations—and is important for maintaining an accurate perception of reality. (You walk up close to the tree and shine a light on it. Its shadow looms large. Someone has indeed painted a swastika on a tree in your front lawn. How do you feel about your city now?)

☟

Kolkata is restoring its crumbling historical edifices in an effort to keep pace with the impressive growth of cities like Delhi and Mumbai. Many think it’s not going to survive. I walk barefoot on the red cement floors of the house my grandmother was born in. It has been made into a museum because it is also the ancestral house of Swami Vivekananda, her mother’s great-great-uncle. He is celebrated for popularizing Hinduism in the west, helping to move it from a loose collection of animist beliefs toward something resembling monotheism. I look for the bed that they were both born in but it’s not open to the public. The guard explains that it’s closed off due to concerns with “terrorism.” Outside on the street, a young girl grabs my arm and opens her mouth to show me that her tongue has been cut off. That night, I have strange, vivid dreams.

A dream is an experimental theater for the brain to carry out predictive activities that reduce the complexity of its cognitive model. When a model is too complex, it loses insight and fixates on irrelevant data instead of the underlying relationship of the information. If we suddenly stopped dreaming, our waking existence would quickly begin to resemble being on psychedelic drugs, with the random noise in the environment taking on inappropriate significance.

Dreams occur during REM sleep, when the brain stops participating in the feedback-feedforward loop of prediction error coding using outside stimulus. It instead projects its own virtual-reality simulation of the world to act as a sandbox for synaptic pruning. Synaptic pruning smooths out the noise in the connectome so that the most important networks are reinforced. The seeming contradiction between model simplification and the curious arabesques of dream logic can be explained with the reminder that very simple models—like bird murmurs—can nevertheless produce peculiar and spectacular outputs. By running a series of random virtual inputs through this internal model, the brain enhances its ability to respond to a variety of different situations in waking life.

I visit a school run by my mother’s non-profit. A swarm of mosquitos hover over the class in a black shadow. Subhen Mama, my very first art teacher, is teaching a group of children how to draw. A disjointed piece of his skull protrudes from his forehead, the result of a traffic accident that left him unable to hold a pencil for a long time. The children gather around me, at once curious and shy. I ask for paper and something to draw with. There’s an immediate scramble as they race to retrieve their sketchpads and pastels. I ask them what I should draw. “A lady with a pot of water on her head!” they decide right away. I start drawing a lady with a pot of water on her head—they are very encouraging. “It’s coming out so good!” they say. I start making her face green and they burst into laughter. “What?” I feign offense. “Haven’t you ever seen a green lady before?”

Just as our bodies use dreams to create a more generalizable model of reality, human culture uses creative constructs to produce possible shared futures. The free-association stage of creative brainstorming mimics the slippery process of dreaming, allowing us to run our own unique inputs through the various themes of the human experience: love, courage, brotherhood, coming of age, and loss.

Yet so much of what we learn is locked in a black box. A fetus dreams nearly non-stop for the last 30 weeks of gestation. What does it dream about? As its developing body twitches against the walls of the womb, the fetal brain receives signals from proprioceptors, or sensors in the muscles that create a mental map of the position of the body in space. Proprioceptors teach the fetus how to understand things like orientation, pressure, muscular cause and effect, and other basic types of positional information. These lessons are deeply abstract and embedded in the unconscious, like the signals in a canvas layered with shades of blue paint.

☟

"Hare Krishna Hare Rama" blares through the speakers in the cramped red sedan as we drive out of Kolkata through townships and villages toward the jungles of Sundarban. A thick gray fog obstructs the tops of the banana and palm trees lining the road. After the second hour the droning music has taken on a hallucinogenic quality. Goat carcasses hang in streetside stalls with the organs prominently displayed. All of a sudden our car is surrounded by a throng of women and girls in cream and red saris warbling ululations. Men with drums march alongside with sanai blaring from speakers. The car crawls through a river of people. I scream as a gunshot rings out. It’s a confetti cannon.

Life in India demands tolerance of ambiguity. Tanizaki praised this aspect of Eastern aesthetics:

Shadows are beautiful because they emphasize the source of light and the limits of its reach. Obstructions produce shadows and give them their shape. But an empty, brightly lit room doesn’t become beautiful when shadows are artificially painted into the corners. There are plenty of real shadows to chase.

We eat shrimp curry with the people of the Sundarban islands on a boat in the delta. The sun is neon pink floating in a haze of lavender. A passionate young woman is talking about her mission to empower farmers. She reminds us that while we need doctors and lawyers once in a while, we need farmers three times a day. Blooms of big white jellyfish pulse alongside the boat like beating hearts. Crocodiles sunning in the mud slide lazily into the emerald water as we pass by. A man who has donated his own land and money to start a school for children on his island implores me to help him bring medical care there. “The government doesn’t provide for us—we only have quack doctors here,” he says. I feel helpless. We briefly discuss telemedicine as we land on the last island before the Bay of Bengal stretches for miles toward Bangladesh. Sensing our vibrations, a carpet of red crabs scuttle into holes in the sand.

On our way home toward the city we pass dozens of minor religious celebrations lit in green and purple lights. Priests pelt the car with disks of jaggery that fall into our laps like blessed moons. Painted idols are pulled in chariots from village to village, purposeful sentinels obstructing direct access to the divine. Their clay bodies absorb prayers and provide, in return, the opportunity to come together and be close, to dance, sing, and eat sugar lit by neon lights in the shadows of the forest.